.htm_cmp_cactus010_hbtn.gif)

![]()

Personal

How far back can one remember things? The remotest experiences are often those which have a emotional 'charge' attached to it. A specific incident or happening is linked to those first and later memories. I still have a vivid recollection of a first incident that happened when I was about four years old. Because of the German invasion in Poland etc. my father was in what was called the mobilisation, meaning that every male up to the age of 50 were all brought under arms. He was with the infantry and as was customary in those days, he and other soldiers were quartered with a Dutch farmer in the village of Kesteren. That also had to do with the military horses which were stabled with the selected farmers. My father saw a lot or horse dung during that time, but never came into action. When the nazi hordes flooded our small country the war was ended in a couple of days. Every fortnight my mother and I visited him, usually on a Saturday. It always was a joyful occasions with all the soldiers and the other visiting wives. The farmers usually did not object to that peaceful military invasion as they were compensated for their trouble and also welcomed the change of things, the liveliness brought about by the young soldiers. On one Saturday when they were all having coffee, including the farmer and his wife I decided to a little unattended reconnoitring on my own and in no time at all ended up to 'make friends' with the chained yard dog, a big black Bouvier. Unfortunately I came within his reach and was grabbed and bitten all over. Out of pure joy over this unexpected exercise the big dog also broke his chain. Everybody came running but the damage was already done. Instinctively I seemed to have pressed my chin to my chest as the dog went for the throat and that was my luck they told my parents later. The only doctor in the village stitched the torn flesh and tended to my cuts and bruises. The only set back was that on every Saturday he used to be as drunk as a Tempelier, as the saying goes. So when back in Rotterdam on Monday again my mother took me to our doctor. He seemed to have asked: ''Which butcher did do that stitching job? But he is a boy so it is not necessary to do anything about it'. Thank your very much! Before passing out I can still remember the enraged dog tossing me around like a rag doll. I have often dreamt of that huge black shape dooming up unexpectedly and 'doing things' to me. The result was that I have been afraid of dogs, any size, small, medium or big, for a long time, getting out of their way as far as I could.

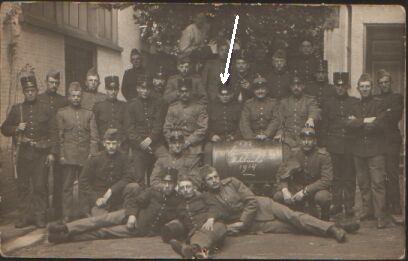

The next inerasable memory was the bombardment of the city of Rotterdam by the nazi criminals in may 1940 not too long after that first incident. The bombardment was the punishment for withstanding the invasion of our country for more than four days and so fouling up the nazi's little agenda. The Germans had figured that they could run us over in one or two days. The Dutch had hoped and advocated that they could remain in a neutral position again. After all we were not a nation of warriors, on the contrary. We managed to remain neutral once before during the first World War and the Dutch tried to do a repeat of that status. My grandfather also took part in the mobilisation of the first World War 1914 - 1918.

The written text says "Ter herinnering Mobilisatie 1914", meaning in English "In remembrance Mobilisation 1914"

The country was not heavily armed, almost to show that we were serious about our neutral position, why should we arm ourselves heavily? Had not Hitler also promised us not to invade our country..... The bombardment of defenceless civilians, like in the case of Rotterdam, was meant to speed up things by breaking the resistance of the population. In that respect the Germans were very successful. The Dutch threw the towel into the ring after that very fine occasion in which many thousands of civilians, including many children, were killed. The entire densely populated inner city of Rotterdam was annihilated. How low can one get.... When the Germans entered the city a small number of Dutch Royal Marines, who did not want to give up, still defended the Maas-bridge connecting the northern and southern part of the city. They were hidden underneath the bridge's structure consisting of many heavy beams and cross beams and had an almost bullet-proof shelter from the Germans' continuous gunfire barrage. Due to lack of ammunition they had to surrender after a couple of days. The Germans were very surprised and ashamed to find that only a handful of Royal Marines surrendered as the number of them seemed to be much larger, as they shot from continuously changing positions.

My second set of memories are that my parents during the bombardments carried me over the burning streets to seek shelter with my grandparents who lived close by in a house with a cellar. The cellar was already strengthened with big poles by my grandfather, who rightly so expected that the German invasion would occur anyway any day, although the Dutch government had informed the population that everything was under control and that everyone could sleep quietly, have nothing to fear, as the Government was watching over them. After the surrender they were amongst the first to flee to unoccupied England, to form a government in exile and direct the resistance from there..... I can still remember the red glow of the burning city, the screeching sound of the attacking diving German Junker bombers followed by whistling sounds and then by heavy, thudded explosions, the inherent trembling of the whole house, rattling of doors and windows, the wail of the air defence sirens, the small amount of anti aircraft flak trying to hit the Junker bombers, the crying out of people in the streets and especially the distinct smell of burning. I remember to register it all rather quietly and with awe, taking in the scene and sounds even at that young age. However, I remember also that what disturbed me most was not so much the things happening around me, but the sheer panic which I sensed with my parents. Once inside the cellar we found that neighbours and other family members were also present. That routine repeated itself many times over later. Sometimes we could not leave the house in time due to the late siren warnings and the very close bombing and then huddled in the staircase, which was by rumour the safest place in a house.

A painting of R.S. Bakels with a part of the bombed city of Rotterdam in 1940. The burnt out Laurens Church is sticking out of the ruins as a sore finger. (Algemeen Dagblad 02-28-2002)

The only one in the family who always kept her cool was my grandmother. Even during the bombardments as far as she was concerned, business was as usual. She refused to go down into the cellar and remained upstairs, unperturbed. No matter how much the family members begged her to join them or how close the bombs would fall. Her simple theory was that once a bomb would hit the house everybody, including those in the cellar, would be killed anyway. She used to repeat this statement quite often it seemed. And that was the best way to go, all together in her opinion. So why bother? It would seem that her estimation of the shelter's safety and thus my grandfather's efforts in constructing it, was rather low and I am inclined to think she was quite right. She made herself useful with boiling tea, making sandwiches for the cellar crew and if the time was right, preparing nutritious meals.

This a picture is of my grandmother, taken between 1905 -1910

She was born in Rotterdam July 26, 1888

From that moment memories are on and off, mostly related to air raids, the constant drone of scores of allied bombers heading for Germany. We became experts in estimating where the planes were friend of foe. The sirens often started wailing in the middle of the night. In the end we did not even bother to sprint for my grandfather's cellar as we could hear from the steady and remote drone that they were just passing over. We then used to look out of the windows at the dark sky which was shredded to pieces by many searchlights trying to highlight the bombers. And the flak bursts all over the sky. We never saw a bomber being hit probably due to their altitude. All street lights were extinguished in the evening and during the night during the war. No lights were allowed, so curtains had to be drawn tightly shut, otherwise you would get a visit and a red card. A somewhat major incident happened in about 1942. I was sick and lying on a make-shift bed in the front living room on the third floor when I actually saw something big and black streaking down from the skies immediately followed by a tremendous explosion. No warning, no sirens nothing. As they say this was indeed "out of the blue". It appeared that a house about 100 meter away was cut out of a row of houses quite neatly, almost surgically. We never heard the story, but it must have been a German bomber loosing one of the bombs it carried by accident or something like that. Furthermore there were V-1 and later V-2 rockets launched from a hidden site in a green park (Kralingse Bos) situated in the eastern part of Rotterdam and aimed at London. Usually it was not a big problem as they streaked up and already high over the city on their westbound journey. But one in some many rockets went wild, out of control and then it was every bodies guess were it would come down. On an early Sunday morning one came down in the city in the Blijdorp area. We rolled almost out of our beds from the explosion, so intense it was. Apart from the bomb inside this hideous contraption almost none of the rocket fuel had been burnt. Others came shrieking over very low, right above our heads and on an erratic, wavering course. The sound it produced cannot be described, it was the sound of a world gone totally mad. I can still remember that on one particular occasion, in the middle of the day and always without warning a rocket came over so low that I could smell the fumes of it. We were out in the street and had not time to take cover, so fast it all happened.

What I hated most in those days was standing in line for food. Apart from the fact that it was very difficult for me at that age to be in one spot for a prolonged period of time, their was also another reason for that dislike. Family members usually took turns as the waiting time often was more than 4 hours. Being a little boy sometimes grownups behind me slowly but surely stepped in front of me. I protested than heavily but they did it anyway. When I was relieved by one of my parents there used to be a lot anger and pushing around as they had noted my place in the line.

Deze opname roept ongetwijfeld bij vele Rotterdammers herinneringen op aan een tijd van ontbering en ellende. Op het Burgemeester Meineszplein (niet zover van waar ik woonde aan het Middellandplein 18 in Rotterdam-West) staat een lange rij wachtenden, van wie sommigen op klompen (schoenen waren toen al een grote luxe), om hun karige rantsoen in ontvangst te nemen. Dit bestond rond eind januari 1945 uit 500 gram brood, 1000 gram aardappelen en 125 gram peulvruchten, in totaal zo'n 2500 calorieŽn, per persoon per week. Al met al komt het erop neer, dat ongeveer voor een week werd verstrekt wat men gemiddeld per dag nodig heeft. Vaak was het op de bon toegewezen rantsoen niet eens te krijgen. Groenten waren nog moeilijker te bemachtigen. Toen de heer J.F.H. Roovers eind november 1944 deze opname maakte, lagen de razzia's van 10 en 11 november nog vers in het geheugen. Alle mannen in de leeftijd van 17 tot en met 40 jaar werden t.b.v. de 'Arbeitseinsatz' naar Duitsland gedeporteerd. De achtergeblevenen zijn verstoken van gas en elektriciteit en staan aan de vooravond van een verschrikkelijke hongerwinter. (foto en tekst onder nr. 26 uit 'Groeten uit Rotterdam-West' van H.A. Voet en A.Tak)

This picture will bring back, without any doubt, a lot of memories to the citizens of Rotterdam who had to experienced the hardships and utter misery of that time. On the 'Burgemeester Meinesz Square" (only a short distance from where I used to live in Rotterdam) a ( as leather shoes had become a luxury by then), to receive their meagre rations. At the end of January, 1945 this consisted per person and to last a week, out of 500 grams bread, 1000 grams potatoes en 125 grams pulse (beans etc.). In total this amounted to 2500 calories per week per person. All in all grown ups had to live a week on a one day's ration. Often the food supplied against rationing coupons was not even available. Vegetables were even harder to get. When the photographer took this picture at the end of November 1944, the so called razzia's or round-ups, where still etched in everybody's memory. On November 10 and 11, 1944 men between 17 and the age of up to and including 40 years were deported to Germany for the so called 'Arbeitseinsatz'. (A program to replace the German males, who had either been killed in the war in great numbers by that time or had been called to arms. It was in fact pure slavery. They were put to work at the German home front, in the weapons industry and on farms. Many never returned as they were killed during the Allied bombardments in Germany, also men I used to know in my street and a number of the fathers of children in my school.)

On top of that the families left behind were devoid of gas and electricity and are at the eve of a terrible hunger-winter. (photograph and text as shown under nr. 26 in the booklet 'Greeting from Rotterdam-West' by H.A. Voet en A. Tak.)